A Path to Universal Neural Cellular Automata

Exploring how neural cellular automata can develop continuous universal computation through training by gradient descent

Cellular automata have long been celebrated for their ability to generate complex behaviors from simple, local rules, with well-known discrete models like Conway’s Game of Life proven capable of universal computation. Recent advancements have extended cellular automata into continuous domains, raising the question of whether these systems retain the capacity for universal computation. In parallel, neural cellular automata have emerged as a powerful paradigm where rules are learned via gradient descent rather than manually designed. This work explores the potential of neural cellular automata to develop a continuous Universal Cellular Automaton through training by gradient descent. We introduce a cellular automaton model, objective functions and training strategies to guide neural cellular automata toward universal computation in a continuous setting. Our experiments demonstrate the successful training of fundamental computational primitives — such as matrix multiplication and transposition — culminating in the emulation of a neural network solving the MNIST digit classification task directly within the cellular automata state. These results represent a foundational step toward realizing analog general-purpose computers, with implications for understanding universal computation in continuous dynamics and advancing the automated discovery of complex cellular automata behaviors via machine learning.

Introduction and Background

Cellular Automata (CA) represent a fascinating class of computational models that have captivated researchers across disciplines for their ability to produce complex behaviors from simple rules

Several discrete CA models, including Conway’s Game of Life

In recent years, the development of continuous CA has bridged the gap between discrete models and the analog characteristics of the real world. Notable examples include Lenia

The lack of discrete states and well-defined transitions makes it harder to encode symbolic information reliably — slight perturbations can lead to significant divergence over time, undermining the stability required for computation. Moreover, continuous models often exhibit smooth, fuzzy dynamics that make it challenging to design modular components like wires, gates, or memory elements with predictable behavior. What was already a laborious task in discrete CA becomes more difficult, if not practically impossible, in the continuous domain, highlighting a fundamental challenge in building efficient analog computers.

Neural Cellular Automata (NCA) represent a paradigm shift by replacing hand-crafted rules with neural networks trained via gradient descent

It is important to note that the use of NCA in computational settings has precedent. Matrix copy and multiplication tasks were first implemented with NCA by Peter Whidden

Our work connects to analog computing and neuromorphic systems, which leverage biological principles like local computations

In this work, we explore the potential of the Neural Cellular Automata paradigm to develop a continuous Universal Cellular Automata

Our approach introduces: (1) a novel framework disentangling “hardware” and “state” within NCA, where CA rules serve as the physics dictating state transitions while hardware provides an immutable and heterogeneous scaffold; (2) objective functions and training setups steering NCA toward universal computation in a continuous setting; (3) experiments demonstrating the training of essential computational primitives; and (4) a demonstration of emulating a neural network directly within the CA state, solving the MNIST digit classification task. These results mark a critical first step toward sculpting continuous CA into powerful, general-purpose computational systems through gradient descent.

Methods

We leverage the CAX

General Setup

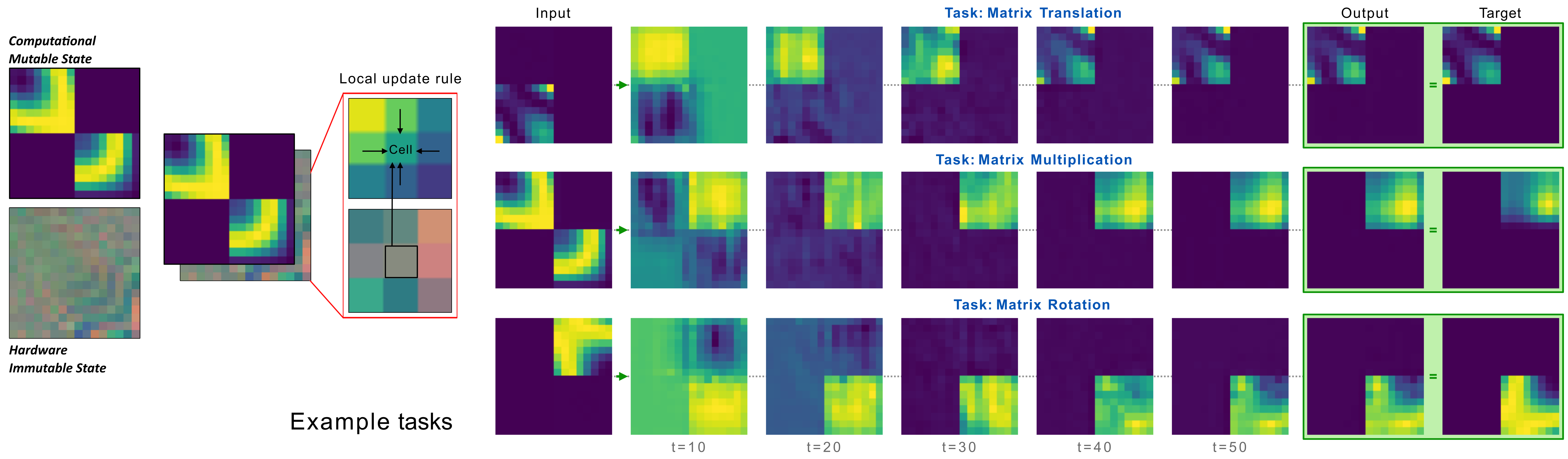

Our framework demonstrates neural cellular automata’s capability to act as a general computational substrate. We introduce a novel architecture that partitions the NCA state space into two distinct components:

-

Mutable state: The main computational workspace where inputs are transformed into outputs. This state changes through time during task execution, governed by NCA rules.

-

Immutable state: A specialized hardware configuration that remains fixed during any single experiment. This hardware can itself be monolithic (trained as a block, the same shape as the entire grid), modular (created from different specialized components for each task specific instance), or even generated from a graph-based hypernetwork (see Future directions). This is learned across training but fixed in any duration of a single experiment / task instance.

This separation enables a two-level optimization: at the global level, we train a general-purpose NCA rule to support diverse operations, while at the task-specific level, we optimize hardware configurations. The system adapts its dynamics using the local available hardware, similar to how different components on a motherboard enable different functions, using the same underlying physical substrate.

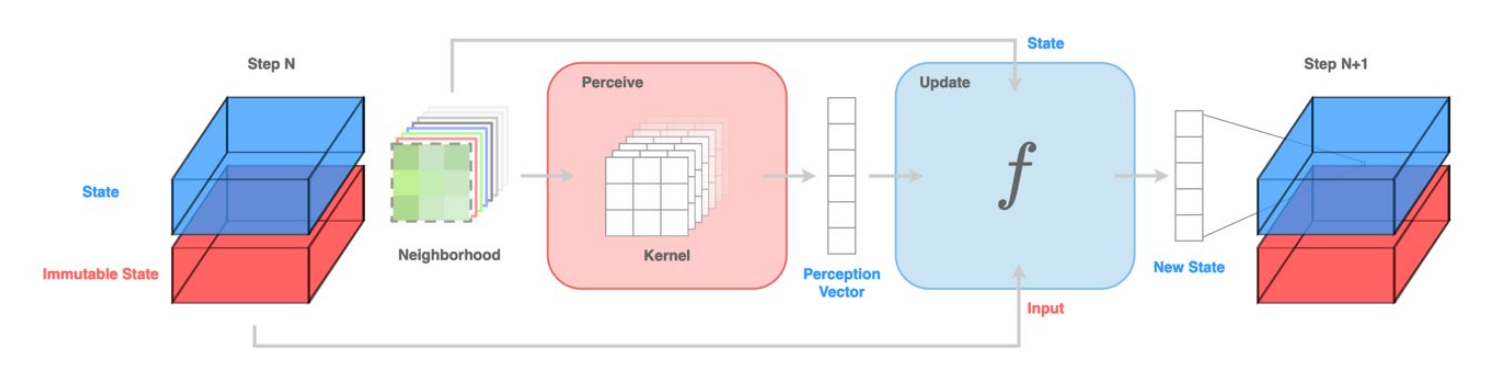

Neural Cellular Automata

Our NCA models solve tasks directly within their mutable state through local cell interactions, parametrized by a neural network with two key components:

-

Perceive Function: Gathers neighborhood information through learnable convolution filters applied to the immediate vicinity, transforming input states into a higher-dimensional perception vector.

-

Update Function: Utilizes the perception vector and local hardware vector to update each cell’s state. We use an attention-based update module that calculates state updates by conditioning perceived information on the local hardware.

The key innovation in our update function is an attention mechanism that allows each cell to selectively route its computation based on its local hardware. Here’s how it works:

-

Each cell receives a perception vector $P$ (local spatial patterns) and a hardware vector $I$ (its immutable state).

-

The hardware vector $I$ activates different “computational modes” through an attention mechanism: $\alpha = \text{softmax}((I \cdot W_{\text{embed}}) / T)$, where $W_{\text{embed}}$ is a learned embedding matrix and $T$ is a temperature parameter controlling the sharpness of the activation.

-

The perception vector $P$ is simultaneously processed through $N$ parallel pathways (implemented as MLPs), producing potential update vectors $V_h$ for each pathway.

-

The final state update is computed as a weighted mixture of these pathways: $\Delta S = \sum_{h=1}^{N} \alpha_h V_h$, with the cell’s state updated residually: $S_{t+1} = S_t + \Delta S$.

This design allows the NCA to adapt its behavior dynamically based on the local hardware—cells in input regions might activate different computational pathways than those in output regions or computational zones. The result is a flexible computational substrate where the same underlying rule can perform diverse operations depending on the hardware context.

Hardware (Immutable State)

We explored different approaches for designing specialized hardware configurations:

Monolithic Hardware

Our initial implementation used task-specific parameters with the same spatial dimension as the computational state. While successful and visually interpretable, this approach lacks generalizability across different spatial configurations and matrix sizes: concretely the a new hardware configuration needs to be trained for each new matrix size and placement.

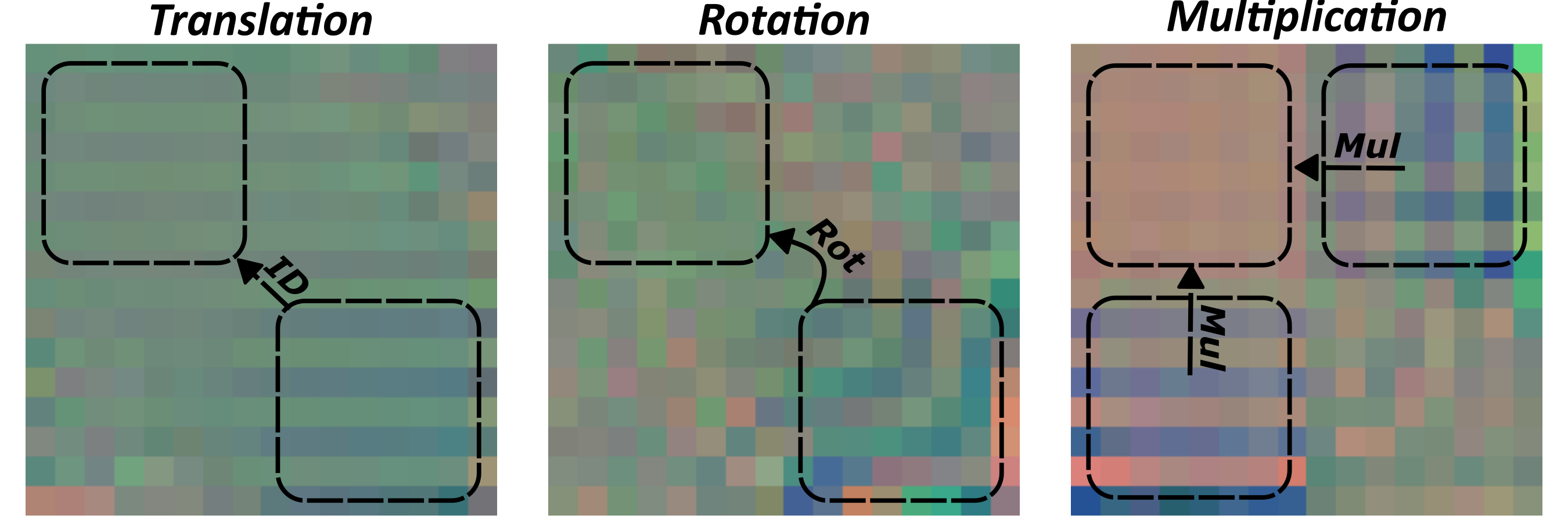

Modular Hardware

To address these limitations, we developed a modular approach with three purpose-specific hardware components:

- An input embedding vector marking cells that receive inputs

- An output embedding vector marking cells that will serve as output

- A task embedding vector enabling the NCA to recognize the required transformation

These components are assembled for each task instance, balancing the scale-free nature of NCAs with the need for specialized hardware. This approach enables zero-shot generalization to unseen task configurations and composite task chaining.

Tasks

We implemented a flexible framework of matrix-based operations to train robust and versatile NCA models:

Matrix Operations:

- Identity Mapping: Moving a matrix to a different location

- Matrix Multiplication: Computing C = A × B

- Transposition/Rotation: Computing B = A^T or 90° rotation

- Element-wise Operations: Computing C = A · B

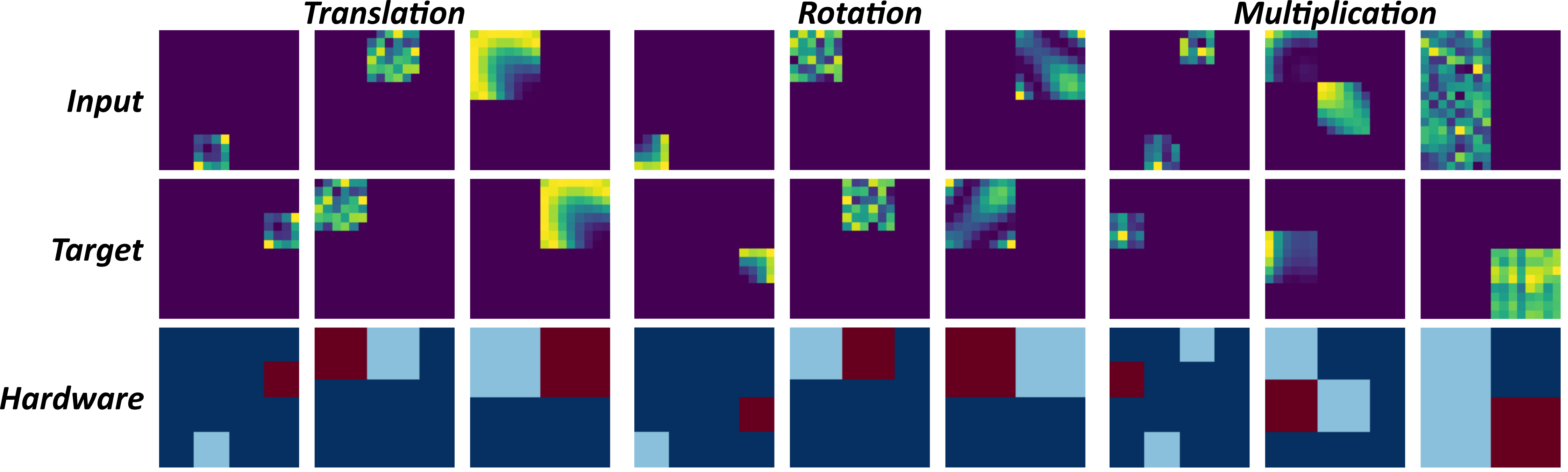

We used diverse input distributions (uniform, Gaussian, spatially correlated, discrete-valued, and sparse) to prevent overfitting to specific patterns. With the modular hardware approach, we enabled flexible placement with dynamic positioning, variable matrix sizes, and multiple inputs/outputs.

Training

Our training framework simultaneously optimizes a single NCA rule across diverse task instances. Each task instance is represented by an initial state, a target final state, and a mask indicating relevant evaluation regions.

During training, we sample batches containing various tasks. For each instance, the NCA evolves the initial state over discrete time steps. We compute loss (typically masked MSE) between the final and target states within relevant regions, then update parameters using gradient-based optimization.

Parameters for the shared NCA rule and shared hardware components are updated based on gradients across all tasks, while task-specific modules are updated using only their corresponding task gradients. This joint optimization encourages a versatile NCA capable of executing multiple computational functions by adapting to the presented hardware.

Experiments and Results

Task Training

Joint Training

Our Neural Cellular Automata successfully mastered various matrix operations simultaneously through a shared update rule architecture with task-specific hardware components. This demonstrates that a single NCA can develop general computational principles that apply across different matrix tasks.

By simultaneously learning diverse operations (multiplication, translation, transposition, rotation), the model demonstrates mastery of a complete algebra of matrix operations—the essential building blocks for more complex computation. This multi-task foundation enables more sophisticated applications, including our MNIST classifier emulation.

Downstream Tasks Fine-tuning

A key advantage of our architecture is that once the NCA is pre-trained, new tasks can be accommodated by fine-tuning only the hardware configurations while keeping the core update rules frozen. In our experiments, this approach increases training speed by approximately 2x compared to full model retraining.

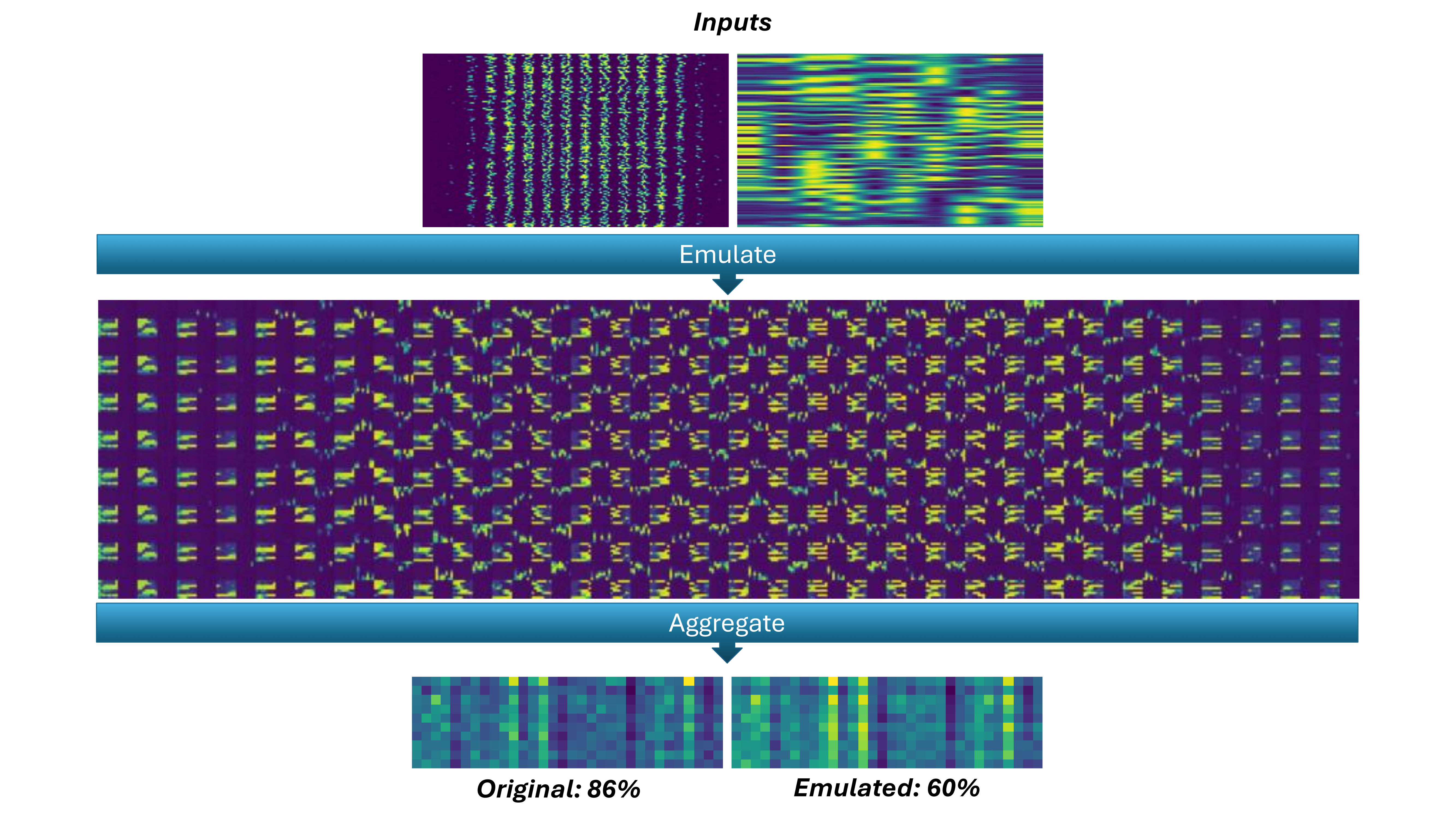

MNIST Classifier emulation

We demonstrated a practical application by using our NCA to emulate a neural network directly in its computational workspace. We emulated a single-layer MLP solving the MNIST digit classification task.

First, we pre-trained a simple linear network to classify MNIST digits with sufficient accuracy. Our NCA model was pre-trained on smaller 8×8 matrix multiplication tasks. Since MNIST classification requires larger matrices (784×10), we implemented block-matrix decomposition, fragmenting the classification into multiple smaller operations that fit within the NCA’s constraints.

The NCA processed each block operation in parallel, after which we aggregated the results to reconstruct the complete classification logits. While we observed some accuracy degradation due to error propagation (60% accuracy for the emulated classification compared to 84% for the original), this demonstrates that neural network emulation via NCA is feasible.

This has significant implications for analog and physical computing. If our NCA’s update rules were implemented as physical state transitions, this would represent a pathway toward physical neural network emulation without reverting to binary-level operations.

Future directions: task composition and neural compiler

The modular hardware approach enables the creation of out-of-distribution tasks through component composition. We can design novel computational scenarios that the NCA wasn’t explicitly trained on, such as duplicating a central matrix into multiple corners.

This framework opens the path toward complex composite tasks created through sequential chaining of primitive operations. For example:

- Start with an input matrix and distribute copies to corner positions

- Replace the hardware configuration to redefine these targets as inputs, then perform matrix multiplication toward a third corner

- Update the hardware again to rotate the resulting matrix and return it to the original position

While such sequences may appear simple, they demonstrate a critical capability: the NCA can execute complex algorithmic workflows through sequential hardware reconfiguration. This composite task chaining highlights the importance of stability in achieving composable computations.

We propose a dual-timestep approach to neural compilation:

- At the neuronal timestep, the NCA’s mutable state evolves according to update rules

- At the compiler timestep, hardware parameters are reconfigured to guide high-level procedural steps

This separation mirrors classical computer architecture but within a continuous, differentiable substrate. As this approach matures, it could enable direct compilation of algorithms into neural cellular automata, combining neural network flexibility with programmatic precision.

Graph-based hardware hypernetwork

Taking the neural compilation idea further, we’re developing a more principled graph-based hardware generation framework that offers significant improvements in flexibility and scale-invariance. This approach leverages a higher-level task representation abstraction where computational operations are modeled as a graph—nodes represent input and output regions while edges encode specific transformations between them.

At the core of this system is a Hardware Meta-Network consisting of two key components:

-

A Graph Neural Network (GNN) encoder processes the task graph structure. Nodes contain normalized spatial information about input/output regions, and edges represent operations (matrix multiplication, rotation, etc.) to be performed between regions. Through message-passing layers, the GNN distills this representation into a fixed-dimensional latent task vector capturing the computational requirements.

-

This latent representation then conditions a coordinate-based hypernetwork that generates hardware vectors for every spatial location in a scale-free manner. Using positional encodings, the hypernetwork creates spatially varying hardware patterns that guide the NCA’s dynamics. Crucially, this approach maintains spatial invariance—task specifications are normalized relative to grid dimensions, enabling automatic adaptation to different grid sizes and region placements.

This graph-based representation provides an intuitive interface between human intent and NCA computation. Users define tasks through natural graph specifications (inputs, outputs, operations), and the meta-network translates these into appropriate hardware configurations. This effectively creates a true compiler between human intent and the NCA’s computational capabilities, allowing for more sophisticated definition of task chaining and temporal hardware evolution.

The graph structure enables rich extensions beyond our initial implementation. Tasks can be ordered through edge attributes for sequential execution planning. Dynamic hardware reconfiguration becomes possible by modifying the task graph over time, creating a secondary dynamics layer complementing the fast neural dynamics of the cellular automaton. This hierarchical temporal structure—fast neural dynamics for computation, slower hardware dynamics for program flow—mirrors traditional computing architectures’ separation of clock-cycle operations and program execution, but within a unified differentiable framework.

This approach represents a promising path toward more efficient, adaptable continuous computational paradigms that could fundamentally change how we think about programming NCA-based systems and potentially other emergent computational substrates.

Conclusion

The exploration of universal computation within cellular automata has historically been confined to discrete systems, where models like Conway’s Game of Life and Elementary Cellular Automata have demonstrated the remarkable ability to emulate Universal Turing Machines. However, extending this capability to continuous cellular automata presents significant challenges, primarily due to the absence of discrete states and the inherent instability of smooth, analog dynamics. In this work, we have taken pragmatic first steps toward overcoming these hurdles by leveraging NCA as a substrate for developing universal computation in a continuous domain. By employing gradient descent to train NCA rules, we have demonstrated a pathway to sculpt complex computational behaviors without the need for manual rule design, shifting the burden of discovery from human ingenuity to machine learning.

Our results illustrate that NCA can successfully encode fundamental computational primitives, such as matrix multiplication and inversion, and even emulate a neural network capable of solving the MNIST digit classification task directly within its state. These findings suggest that NCAs can serve as a bridge between traditional computing architectures and self-organizing systems, offering a novel computational paradigm that aligns closely with analog hardware systems. This linkage is particularly promising for designing efficient computational frameworks for AI models operating under constrained resources, where energy efficiency and robustness are paramount. Rather than training entirely new rules for each task, our approach hints at the possibility of discovering optimal hardware configurations that exploit the fixed physical laws governing these substrates, enabling meaningful computations with minimal overhead.

Looking forward, we believe this work lays the groundwork for transformative advancements in computational science. By automating the discovery of general-purpose computers within diverse physical implementations, NCA could revolutionize how we harness novel materials and systems for computation, potentially leading to ultra-efficient analog hardware systems or computational paradigms that scale linearly with resource demands. While challenges remain — such as stabilizing continuous dynamics for reliable symbolic encoding and scaling these systems to more complex tasks—the potential of NCA to unlock universal computation in continuous cellular automata opens new avenues for exploration. Ultimately, this research not only advances our understanding of computation in continuous dynamics but also paves the way for the next generation of adaptive, energy-efficient computing technologies.

Author Contributions

Gabriel Béna and Maxence Faldor contributed equally to this work. Maxence Faldor initiated the project, conceived its central ideas, including the concept of state and immutable state for hardware representation. He also developed the initial software library and experimental design. Gabriel Béna provided crucial feedback on these foundational ideas, developed the tasks setup, led the development of the compiler and the Graph Neural Network (GNN) components, conducted the extensive experiments, and was the primary author of the project website. Dan Goodman and Antoine Cully supervised the project, offering guidance, insightful discussions, and contributing to brainstorming sessions.

Acknowledgements

We thank Arthur Braida for his insightful discussions and feedback, mainly about computing with continuous, analog substrates.

Citation

For attribution in academic contexts, please cite this work as

Béna, et al., "A Path to Universal Neural Cellular Automata", Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO '25 Companion), 2025.BibTeX Citation

@article{bena2025unca,

title = {A Path to Universal Neural Cellular Automata},

author = {Béna, Gabriel and Faldor, Maxence and Goodman, Dan and Cully, Antoine},

journal = {Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO '25 Companion)},

year = {2025},

doi = {doi.org/10.1145/3712255.3734310}

}